There is something as a mother about hearing of a gun in a school. A mother about to send her first baby to middle school. Something that makes my jaw tense and my fingers twitch.

I wrote a few weeks ago about the shooting in Santa Barbara. Because of the connection the story had to my sorority. And then Seattle Pacific University felt even closer, where I have so many overlaps of faith and place. I didn’t think it could get more personal unless it was here in Denver (and we’ve had plenty of our own school shootings to claim). But then a few days ago in Troutdale, Oregon, tucked along the Columbia River between Portland and Hood River, Reynolds High School.

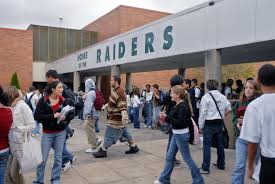

For two years I walked the halls of Reynolds High School, a staff badge around my neck. Despite the fact that I didn’t actually work for the school, I had access to students, my own room with El Programa Hispano on the nameplate in the hall and my own phone extension in the building. My job was funded by a grant to tackle the huge dropout rate of children of migrant workers. The berry farms of Troutdale and the orchards of Hood River had been bringing migrant families to the beautiful river valley for years. And then twenty years ago many of those families stopped being migrant and started putting down roots and the school district was not prepared for them.

So there I was at Reynolds, a white Christian bleeding heart whose expensive private college education landed her a bachelor’s degree in Spanish, translating for school counselors and teachers when they couldn’t communicate with students or their parents. Kids who weren’t even on the margin, they were hiding in the shadows and they didn’t want me to drag them out. They wanted to remain invisible. And I was insisting that they know they were seen. Because my paycheck came from Catholic Charities I felt more free to say that they had always been visible to their Creator.

Toward the end of my second year at Reynolds, Columbine happened. My strongest geographic tethers to this world include Colorado and the Pacific Northwest, where I’ve lived back and forth most of my life. And so it’s been with my connections with the school shootings. Fourteen years ago I watched from states away as a Denver news reporter standing in the middle of a Littleton street covered her mouth to soften the sobs and said, “I’m sorry. I’m thinking about my own kids.” I watched as teachers ran out. And I kept thinking, That could be me. That could be Reynolds. Those could be “my” kids.

My last weeks at the school I’d find myself sitting in my room considering my escape plan. Or in the principal’s office making a phone call to tell parents their son couldn’t wear a trench coat to school. There aren’t words for this kind of madness in my native tongue. In my second language the craziness of the talk was even more obvious as I stumbled to choose words about shootings and copycats and boys not giving the wrong impression. Parents who were used to being confused by our culture and our ways lumped it all into the same ball of American craziness.

And now jump ahead. I live in the land of Columbine and Reynolds High School is back on the forefront of my mind. I again sit states away and wait for the local ten o’clock news to cover the day’s school shooting and am dumbfounded it is not the first story of the night, or the second or even the fourth. Because it almost isn’t even newsworthy anymore. I snuggle in the dark with my two-year old on her mattress on the floor waiting for her breaths to slow and become regular and memories swirl of the gym where I went daily, the front office, the security guards, the parking lot. My morning routine so many years ago where I’d say my prayers of protection as I walked through the mist, my travel mug in hand, into the building to see the invisible kids.

And now the pundits debate gun control policy and mental health resources and armed guards in schools. And I think about the pain. The pain these boys are in to act out to make their invisible hurt public. The pain that screams “NOTICE ME!” and yet goes unspoken until the shots ring out. While others debate important questions of policy my heart centers on how do we bring the invisible into the light, so kids know they are truly seen?

In her new book A Beautiful Disaster: Finding Hope in the Midst of Brokenness, Marlena Graves writes

“We should ask ourselves if we are ever guilty of rendering another invisible. Are there people we choose not to see?…What do we fail to notice on our normal treks to and from home? In what ways are we like the priest and the Levite on the road to Jericho who passed by the man beaten and bruised (see Luke 10:25-37)?”

I’m sure there is a mom out there who can tackle the gun control issue, I am overwhelmed and therefore paralyzed by it. I focus on what I can do. The children in my own house. Their friends. The kids at their schools. How do I not pass by them beaten and bruised? How do I notice that which I’ve failed to notice before? To be that woman that whispers through my actions “You are not invisible”?

Again Marlena,

“We can become a part of overcoming evil with good in our own spheres and by lending whatever kind of a hand we can to those in other spheres. Indeed, one way we know that God sees us is through others. And one way others know that God sees them is through us. We become part of God’s seeing, God’s eyes. And we impart a God’s-eye view to the world.”

And now, where I can, to impart a God’s-eye view to the world.